Football War

| Football War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

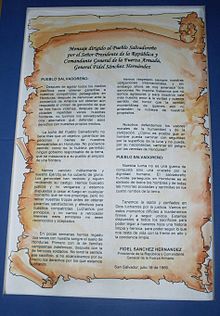

A painting of Fidel Sánchez Hernández (center) in El Amarillo at the Military Museum of El Salvador | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 2,100 (including civilians) | ||||||||

The Football War (Spanish: Guerra del fútbol), also known as the Soccer War or the Hundred Hours' War, was a brief military conflict fought between El Salvador and Honduras in 1969. Existing tensions between the two countries coincided with rioting during a 1970 FIFA World Cup qualifier.[1] The war began on 14 July 1969 when the Salvadoran military launched an attack against Honduras. The Organization of American States (OAS) negotiated a cease-fire on the night of 18 July, hence its nickname, which took full effect on 20 July. Salvadoran troops were withdrawn in early August.

The war, while brief, had major consequences for both countries and was a major factor in starting the Salvadoran Civil War a decade later.

Context[edit]

Although the nickname "Football War" implies that the conflict was due to a football match, the causes of the war went much deeper. The roots were issues over land reform in Honduras and immigration and demographic problems in El Salvador. Honduras has more than five times the area of neighboring El Salvador, but in 1969 the population of El Salvador (3.7 million) was 40 percent larger than that of Honduras (2.6 million). At the beginning of the 20th century, Salvadorans had begun migrating to Honduras in large numbers. By 1969, more than 300,000 Salvadorans were living in Honduras. These Salvadorans made up more than 10% of the population of Honduras.[2]

In Honduras, as in much of Central America, a large majority of the land was owned by large landowners or big corporations. The United Fruit Company owned 10% of the land, making it hard for the average landowner to compete. In 1966, United Fruit banded together with many other large companies[specify] to create the National Federation of Honduran Farmers and Ranchers (Spanish: Federación Nacional de Agricultores y Ganaderos de Honduras, FENAGH). This group put pressure on the Honduran president, Gen. Oswaldo López Arellano, to protect the property of wealthy landowners from campesinos, many of which were Salvadoran.[3]: 64–75

In 1962, Honduras successfully enacted a new land reform law.[4] Fully enforced by 1967, this law gave the central government and municipalities much of the land occupied illegally by Salvadoran immigrants and redistributed it to native-born Hondurans. The land was taken from both immigrant farmers and squatters regardless of their claims to ownership or immigration status. This created problems for Salvadorans and Hondurans who were married. Thousands of Salvadoran laborers were expelled from Honduras, including both migrant workers and longer-term settlers. This general rise in tensions ultimately led to a military conflict.[citation needed]

Buildup[edit]

In June 1969, Honduras and El Salvador met in a two-leg 1970 FIFA World Cup qualifier. There was little to no fighting between fans at the first game in the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa on 8 June 1969, which Honduras won 1–0.[1] However, the second game, held on 15 June 1969 in the Salvadoran capital of San Salvador and won 3–0 by El Salvador, was followed by a uptick in violence.[5] A Honduran fan was shot to death soon after the game, resulting in anti-Salvadoran riots occurring across Honduras and further straining of relations.[6][7]

On 26 June 1969, the night before the play-off match in Mexico City, which El Salvador would win 3–2 after extra time,[8] El Salvador dissolved all diplomatic ties with Honduras, stating that around 12,000 Salvadorans had been forced to flee Honduras in the days following the second match.[1] It further claimed that "the government of Honduras has not taken any effective measures to punish these crimes which constitute genocide, nor has it given assurances of indemnification or reparations for the damages caused to Salvadorans".[3]: 105

War[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

On 14 July 1969, at around 6 PM, the concerted military action began;[7] the Salvadoran Air Force, using civilian aircraft with explosives strapped to their sides as bombers, attacked targets inside Honduras.[9] Salvadoran air-raid targets included Toncontín International Airport, which left the Honduran Air Force unable to react quickly.[6] The larger Salvadoran Army launched major offensives along the two main roads connecting the two nations and invaded Honduras.[10]

The invasion was led by two contingents; a third contingent held strategic positions near the Sumpul River, but never saw combat.[citation needed] The first one was meant to secure the prosperous Sula Valley, while the second marched along the Pan-American Highway toward Tegucigalpa.[10]

Initially, the Salvadoran army made rapid progress, capturing the city of Nueva Ocotepeque and reaching within striking distance of Nacaome. The momentum of the advance did not last, however.[11]

The Honduran Air Force reacted by striking the Ilopango International Airport.[6] Honduran bombers attacked for the first time in the morning of 16 July. When the attack began, Salvadoran anti-air artillery started firing, repelling some of the bombers.[citation needed] The bombers had orders to attack Acajutla, where the main oil facilities of El Salvador were based. Honduran air-raid targets also included minor oil facilities such as the ones in Port Cutuco.[6] By the evening of 16 July, huge pillars of smoke arose in the Salvadoran coastline from the burning oil depots that had been bombed.[citation needed]

Both sides deployed aircraft of World War II-era design.[12] All planes in the engagement were of U.S. origin. Cavalier P-51D Mustangs, F4U-1, -4 and -5 Corsairs, T-28A Trojans, AT-6C Texans and even C-47 Skytrains converted into bombers saw action.[13] On 17 July, Honduran Air Force Corsair pilots Captain Fernando Soto and his wingman Captain Edgardo Acosta engaged two Salvadoran TF-51D Cavalier Mustang IIs which were attacking another Corsair while it was strafing targets south of Tegucigalpa. Soto entered a turning engagement with one Mustang and blew off its left wing with three bursts of 20 mm AN/M3 cannon, killing pilot Captain Douglas Varela when his parachute did not fully deploy. Later that day, the pair spotted two Salvadoran FG-1D Goodyear Corsairs. They jettisoned hardpoint stores before climbing and made a diving attack; Soto set one Corsair on fire only to find its wingman on his tail. An intense dogfight between them ended when Soto entered a Split-S, giving him a firing solution which he used to shoot down Captain Guillermo Reynaldo Cortez, who died when his Corsair exploded.[14][dubious ]

The war was the last conflict in which piston-engined fighters fought each other.[14][15]

Ceasefire[edit]

The Honduran government called on the Organization of American States (OAS) to intervene, fearing that the nearing Salvadoran Army would invade the capital Tegucigalpa. The OAS met in an urgent session on 18 July and called for an immediate cease-fire and a withdrawal of El Salvador's forces from Honduras. El Salvador resisted OAS pressure for several days, demanding that Honduras first agree to pay reparations for the attacks on Salvadoran citizens and guarantee the safety of those Salvadorans remaining in Honduras. A cease-fire was arranged on the night of 18 July; it took full effect only on 20 July. El Salvador continued until 2 August to resist pressures to withdraw its troops. Then a combination of pressures led El Salvador to agree to a withdrawal in the first days of August. Those persuasive pressures included the possibility of OAS economic sanctions against El Salvador and the dispatch of OAS observers to Honduras to oversee the security of Salvadorans remaining in that country. The actual war had lasted just over four days, but it would take more than a decade to arrive at a final peace settlement.

Withdrawal[edit]

El Salvador withdrew its troops on 2 August 1969. There were heavy pressures from the OAS, threatening debilitating repercussions if El Salvador continued to resist withdrawing their troops from Honduras. Honduras guaranteed Salvadoran President Fidel Sánchez Hernández that the Honduran government would provide adequate safety for the Salvadorans still living in Honduras. Sánchez had also asked that reparations be paid to the Salvadoran citizens as well, but that was never accepted by Hondurans.

Consequences[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Both sides of the Football War suffered extensive casualties. Some 300,000 Salvadorans were displaced; many had been forcibly exiled or had fled from war-torn Honduras, only to enter an El Salvador in which the government was not welcoming. Most of these refugees were forced to provide for themselves with very little assistance. Over the next few years, more Salvadorans returned to their native land, where they encountered overpopulation and extreme poverty.[3]: 145–155 The resulting social unrest was one of the causes of the Salvadoran Civil War, which followed approximately a decade later in which 70,000 to 80,000 died and a further 8,000 more disappeared.[1][16]

El Salvador suffered about 900 mostly civilian dead. Honduras lost 250 combat troops and over 2,000 civilians during the four-day war. Most of the war was fought on Honduran soil and thousands more were made homeless. Trade between Honduras and El Salvador had been greatly disrupted, and the border officially closed. This damaged the economies of these nations tremendously and led to the 22-year suspension of the Central American Common Market, a regional integration project that had been set up by the United States largely as a means of counteracting the effects of the Cuban Revolution.[citation needed]

The political power of the military in both countries was reinforced. In the Salvadoran legislative elections that followed, candidates of the governing National Conciliation Party (Partido de Conciliación Nacional, PCN) were largely drawn from the ranks of the military. Having apologized for their role in the conflict, they proved very successful in elections at the national and local levels. In contrast to the gradual democratization process that had characterized the 1960s, the military establishment would exercise increasing control.

Aftermath[edit]

Although it had initiated the war, El Salvador played in the World Cup; it was eliminated after losing its first three matches (USSR, Mexico, and Belgium).[17]

Eleven years after the conflict the two nations signed a peace treaty in Lima, Peru on 30 October 1980[18] and agreed to resolve the border dispute over the Gulf of Fonseca and five sections of land boundary through the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In 1992, the Court awarded most of the disputed territory to Honduras, and in 1998, Honduras and El Salvador signed a border demarcation treaty to implement the terms of the ICJ decree. The total disputed land area given to Honduras after the court's ruling was around 374.5 km2 (145 sq mi). In the Gulf of Fonseca the court found that Honduras held sovereignty over the island of El Tigre, and El Salvador over the islands of Meanguera and Meanguerita.[19]

The dispute continued despite the ICJ ruling. At a meeting in March 2012 President Porfirio Lobo of Honduras, President Otto Pérez of Guatemala, and President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua all agreed that the Gulf of Fonseca would be designated as a peace zone. El Salvador was not at the meeting. However, in December 2012, El Salvador agreed to a tripartite commission of government representatives from El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua that was to take care of territorial disputes through peaceful means and come up with a solution by 1 March 2013. The commission did not meet after December, and in March 2013 stiff letters threatening military action were exchanged between Honduras and El Salvador.[19]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Luckhurst, Toby (27 June 2019). "Honduras v El Salvador: The football match that kicked off a war". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Acker, Allison. Honduras: The Making of a Banana Republic. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1988.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Thomas P. (1981). The War of the Dispossessed: Honduras and El Salvador, 1969 (illustrated ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803210097.

- ^ "El Congreso National decreta la siguiente..." [The National Congress decrees the following...] (PDF). La Gaceta (in Spanish). 5 December 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2015 – via lcweb5.loc.gov.

- ^ Goldstein, Erik (1992). Wars and Peace Treaties, 1816–1991. Routledge. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-203-97682-1. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d Desplat, Juliette (20 July 2018). "World Cup fever at its worst: the 1969 Football War". The National Archives. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b "644. Memorandum From the President's Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger) to President Nixon" (PDF). Office of the Historian. 15 July 1969. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Troops Still Alerted; Soccer 'War' Won By El Salvador, 3-2". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. 28 June 1969. p. 1.

- ^ McKnight, Michael (3 June 2019). "Soccer. War. Nothing More". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b Cable, Vincent. "The 'Football War' and the Central American Common Market" (PDF). International Affairs. 45 (4): 658–671 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Hills, Andrew (27 February 2020). "Light Tank M3A1 Stuart in El Salvadoran Service". The Online Tank Museum. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 2463. ISBN 9781851096725.

- ^ Overall, Mario (July–August 2005). "The Hundred Hour War: Honduras versus El Salvador". Air Enthusiast (118): 8–27.

- ^ a b Lerner, Preston. "The Last Piston-Engine Dogfights". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Jones, Nate (25 June 2010). "Document Friday: The Football War". Unredacted. National Security Archive. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Dutra Salgado, Pedro (22 February 2024). "The 100-hour war between El Salvador and Honduras is famous for starting with a football match – the truth is more complicated". University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "1970 FIFA World Cup Mexico ™ – Groups". FIFA. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Tratado general de paz entre las republicas de El Salvador y de Honduras" [General peace treaty between the republics of El Salvador and Honduras] (PDF). Diario Oficial (in Spanish). 13 November 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2015 – via lcweb5.loc.gov.

- ^ a b Kawas, Jorge (18 March 2013). "El Salvador: Sovereignty issues over Gulf of Fonseca". Pulsa Merica. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Armstrong, Robert and Janet Shenk. (1982). El Salvador: The Face of a Revolution. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 9780861043774

- Diamond, Jared. (2012). The World Until Yesterday. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780713998986

- Durham, William H. (1979). Scarcity and Survival in Central America: Ecological Origins of the Football War. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Kapuscinski, Ryszard. (1990). The Soccer War. Translated by William Brand. London: Granta Books.

- Skidmore, T., and Smith, P. (2001). Modern Latin America (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Walzer, Michael. (1977). Just and Unjust Wars. New York: Basic Books.

External links[edit]

- Salvador-Honduras War, 1969

- Soccer War 1969

- El Salvador vs Honduras, 1969: The 100-Hour War

- Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute (El Salvador/Honduras: Nicaragua intervening), International Court of Justice case registry

- Application for Revision of the Judgment of 11 September 1992 in the Case concerning the Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute (El Salvador/Honduras: Nicaragua intervening) (El Salvador v. Honduras), International Court of Justice case registry

- History of Central America

- El Salvador–Honduras relations

- Wars involving El Salvador

- Wars involving Honduras

- Conflicts in 1969

- Attacks in Honduras

- 1969 in El Salvador

- 1969 in Honduras

- July 1969 events in North America

- 1969 in Central American football

- 1969–70 in Honduran football

- 1969 in Salvadoran sport

- 1969 in Central America

- 1969 in Honduran sport

- El Salvador at the 1970 FIFA World Cup

- 1970 FIFA World Cup qualification

- Honduras national football team

- El Salvador national football team

- Association football controversies

- Politics and sports

- Association football riots